Welcome to the Roaming 20s

How the 2020s echo the 1920s

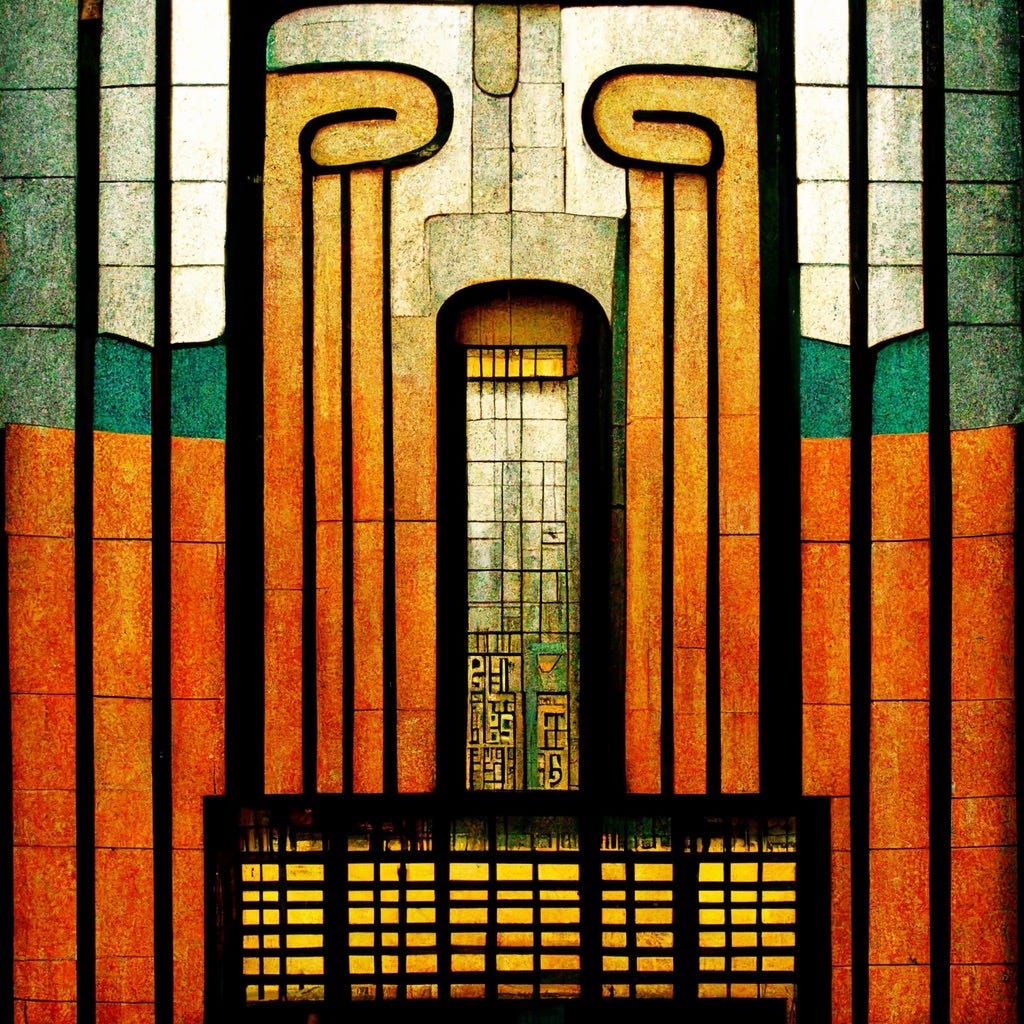

I live in an immaculately restored art deco building in Mexico City. It is one of the few in Condesa that still looks like when it was built a century earlier during the Roaring 20s. Most of the architectural gems from that indulgent era have either collapsed in the 1985 earthquake or fallen into disrepair.

I love it. It indulges my inner romantic and allows me to imagine living a century earlier before. But, like many old buildings in Mexico City, it is sinking into the lake bed. I soon registered its subtle tilt.

Despite its outer opulence, my gut never stops warning me that the foundation is weak. That something is fundamentally off. That it might come crashing down in the next earthquake.

And perhaps because I’m constantly surrounded by echoes of the 1920s, I can’t help but see the similarities that our time has with 100 years ago - and the seismic shifts that occurred in both decades.

History might not repeat itself, but it certainly rhymes. And as we enter the third year of this decade, it’s about time we gave it a name.

I propose The Roaming 20s.

We all know how profoundly the world has changed since 2020. But apart from the obvious - COVID - much of these changes are so far-reaching and happening so fast that we struggle to understand them.

In my 2022 retrospective piece last month, I remarked how this newsletter found an unexpected focus in the controversy around remote-worker gentrification in Mexico City. And while I knew that what was happening in CDMX was indicative of much larger global shifts, I have also struggled to wrap my brain around it - let alone summarize it in a few posts.

But I try because I think it’s important.

I have spent my 15 years since university as a travel commentator. First as a freelance guidebook author, later through my YouTube channel. But from the first time I heard about the coronavirus lockdowns in early 2020, I knew that the world would never be the same again. My job vanished overnight.

Everything is different now. Lockdowns have given way to hyper mobility for some and displacement for many more. Here in Mexico City I have a front row seat to what feels like a larger trend developing before my eyes.

Three years into the 2020s, the defining characteristics of this decade are quite pronounced. Like a century before, we saw a stock market bonanza that seems destined to collapse (and already has). The privileged few are having a grand time while class resentment and nationalist fervor bubble under the surface.

And so we make the most of the time we have.

This has been a defining characteristic of my so-called “Millennial Generation,” which was indelibly marked first by 9/11 and the wars that followed, then by the Great Recession of 2008 that dashed many of our plans for following in traditional career paths.

With record debt levels, stagnant wages and soaring property prices, many decided to trade the American Dream of home ownership for more immediate pleasures. To not put off for later what could be done today.

I suspect this is why remote work has exploded in popularity. It is a very American phenomenon. While I assume that Europeans are also working from anywhere, their traditions of “gap-years” and month-long annual vacations cures them of the urgency so many American Millennials feel.

We are obsessed with optimizing our lives. Whether we have read The Four Hour Workweek or not, most of us still live under its mantra - doing as much as possible with the time, energy and money we have while we can. We love our listicles. We want to know which cities we must visit and where we must eat. We are haunted by our collective Fear of Missing Out.

We are postponing having children in record numbers - if we want them at all. Perhaps it is the climate crisis, or the creeping sense of existential dread that lurks behind what feels like the end of the American Century. Political parties aside, there is an unspoken fear that all of this is going to come crashing down around us, like my tilted apartment on unsteady ground.

So we make the most of it while we can.

In that way, we are not so different from the “Lost Generation” of the Roaring 20s. Two decades of decadence that began with a traumatic shock to the world. Back then, a war. Now a virus.

Granted, being forced to work from home and wear N-95 masks hardly compares to donning gas-masks in trench warfare. But by now we Millennials are accustomed to older generations reminding us of how much easier we have had it than our ancestors. And yet, the parallels remain.

The Great War pulled young men from rural areas and shipped them overseas. Those that returned often moved to cities instead of their villages. Many passed through Paris during the war and decided to return after the armistice. After seeing so much pointless death, they decided to live life with abandon.

In 2020, the coronavirus caused 50% of my generation to abandon their urban apartments and moved back to their family home. When they moved back out, it was often to new cities or places they visited while escaping the lockdowns - like Mexico City, where we are certainly living with abandon.

A century ago, those shell-shocked survivors suffered from an existential crisis that earned them the dubious moniker of the “Lost Generation.”

But what about us? Are we also lost? Perhaps not. But we are certainly wandering. For whatever reason, it seems that many Millennials have grown disillusioned with the American Dream and are swapping it for a more itinerant lifestyle. Trading home ownership for vacation rentals.

Unfortunately, I’m not the only one to call this decade The Roaming 20s. The publication Thrillist apparently launched a branded content series by the same name replete with articles encouraging remote workers to take the leap into digital nomadism. Perhaps because it is sponsored, everything is overly positive to the point of being cringe. Posting stopped shortly after it started.

Nevertheless, our roaming defines this time. Remote work has changed the world almost more than the virus that sparked it. And while bosses try to lull workers back to the office, the shift has already happened.

I am not against remote workers exploring the world. In fact, I encourage it. I believe there are many upsides that can benefit both visitors and locals alike. And while I understand the pain of those displaced by these remote workers, I don’t think calling them a plague or telling them to go home is a solution. Even if some returning to the offices, enough will still find a way to escape the cubicle. And the impact on communities will still be felt.

It’s more helpful to see these changes the shifting geography of the workplace.

Just like how during the industrial revolution, the discovery of fossil fuels decoupled industrial production from the rivers humanity had clung to for millennia. No longer reliant on rivers to turn mills, factories moved elsewhere. New places became winners, while others lost out.

Now that remote work no longer tethers workers to their company headquarters, American cities have seen their downtown cores turn into ghost-towns, while cheaper, sunnier places (with fast internet) have become more popular. Once again, the geography of who wins and loses is shifting.

I find myself in the center of it - and not simply for being in Mexico City, but also for how my previous experiences are strangely coming together. My background in economic development in India, my studies of globalization in school, and my decade as a travel expert and social media influencer are coming together in ways I can only begin to understand.

It no longer feels right to be an unwavering cheerleader for travel. It’s more complex now. When I started my travel writing career, my country was mired in war, forcing nations to be with us or against us. Travel storytelling felt like a much-needed bridge to encourage my fellow Americans to see the world with more nuance. Or as Rick Steves once said: Travel as a Political Act:

Now it feels like this issue is not that too few are traveling - it’s that too many people are going to too few places.

This is usually not intentional or even conscious. After a decade of watching social media influencers create FOMO inducing content encouraging everyone to escape the 9-5 (sorry!) and find some blue ass water, most people are just trying to live out their dreams. But now our very quest for an “authentic” local experience is pushing out the locals who make it “authentic” in the first place and we see how one person’s bucket list can turn into another’s broken dream.

How we work is affecting how we travel in ways we’ve never seen. Visitors are becoming semi-permanent fixtures of cities while skirting the responsibility of being good neighbors. The eternal struggle of the haves-and-have-nots is shifting across borders in unexpected ways that make outdated frameworks for citizenship, taxation and fairness irrelevant and ineffective.

This new privilege of hyper mobility comes with greater responsibility. In the past, perhaps we could close a blind eye to the negative impacts of our two-week vacation. But staying in an AirBNB for a month is something different. We are no longer just passing through, but neither are we citizens who feel responsible to the larger community. And when one month turns into one year, it becomes a serious issue.

Remote work is not going away. But it is pushing many communities to their breaking points. I’ve observed this firsthand in Mexico City, but it is also happening in Lisbon, Bali and beyond. And while newspapers can’t get enough of the narrative of Brooklyn hipsters displacing tortillerías with yoga studios, few of these articles propose solutions.

Which is what I hope to do through The Missive. But it’s hard, because nobody has the answers. Back when I made a living giving travel tips, it was simpler. There were only so many ways to tell someone how to spend 36 hours in a given destination. It was fairly easy to accrue expertise.

But now we don’t even have a map. Most remote workers are aware of contributing to these problems, but not sure what to do. I don’t know either, but I think it is our responsibility to study our changing world thoroughly.

That’s why I chose The End of the World is Just the Beginning as this month’s book club pick. Because an even greater shift is happening in the background - the world as we know it is ending. The American-led system of globalization is breaking apart and we are lurching towards more regionalism and conflict.

How will this affect our futures? Which countries will rise and fall? No one knows. But my gut feeling is that debates around gentrification will seem relatively quaint compared to the seismic shifts we can expect from the rest of this decade. I just hope that from studying the past and analyzing the present, we might be able to glean something about the future.

So, is Mexico the Paris of the Roaming 20s? Perhaps. I’ll dive into that topic soon. I am asking myself other questions such as, which cities will benefit from these shifts? How can cities harness the power of digital nomads to benefit locals as well? How can nomads be better citizens? How is our understanding of citizenship changing? And what is the correct moral framework for navigating a rapidly shift and deeply unfair world?

Comment your thoughts below and I will try to address them on The Missive.

If you enjoyed this post, please share it with a friend or consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support my work and join in our monthly book club discussions. Share your comments, questions and concerns below or in our private subscriber chat (click the link below to join for free).

Until then,

Marko Ayling

Very interesting piece! It seems like the beginning of a much longer, deeper dialogue and social analysis. It was interesting to hear your self-reflection too, based on your experience. Thanks for sharing!

What you shared is the quandary of the times we’re in. I have chosen to pursue dual citizenship in Portugal and live somewhere there that I can be additive. Citizenship means that I will pay taxes and learn the language and history and participate. I live in a very small town right now and every pair of hands is necessary to keep basic institutions functioning. We need to return to a more Peace Corp mentality where you contribute to local culture and communities with your presence. Being a digital nomad has a negative overtone because it implies a one-way relationship (just taking, not giving). Those places are nice because of stable government, local library boards, ngo’s, and organizations that need participants to make a community work. In general, travel is a luxury. I’m thinking a lot about the immigrants at the U.S. border some of whom walked there from South America and Central America. They “traveled” too but was that a fun trip? Probably not so much. We can’t ignore that the world needs us to participate and to give at least as much as we receive no matter where we live.