This post is a day late because yesterday my writing was interrupted by a call from a journalist at Reuters asking to interview me about the very issue I was attempting to address in this article - remote workers and gentrification.

So what’s going on?

In short, the pandemic has unleashed a remote work revolution that has enabled most white-collar workers to become digital nomads. And no city on earth has become more popular with digital nomads than Mexico City. So popular, in fact, that many locals are starting to feel like foreigners in their own city.

It’s a local issue, but it’s also increasingly universal. Therefore, I’d like to address it in a series of newsletters, beginning with an overview of what’s happening here in Mexico City, how you can minimize any detrimental impact of your visit, and what this means for the future of work, globalization, and gentrification.

Let’s start with the first issue - what’s the controversy all about?

I - The Flier

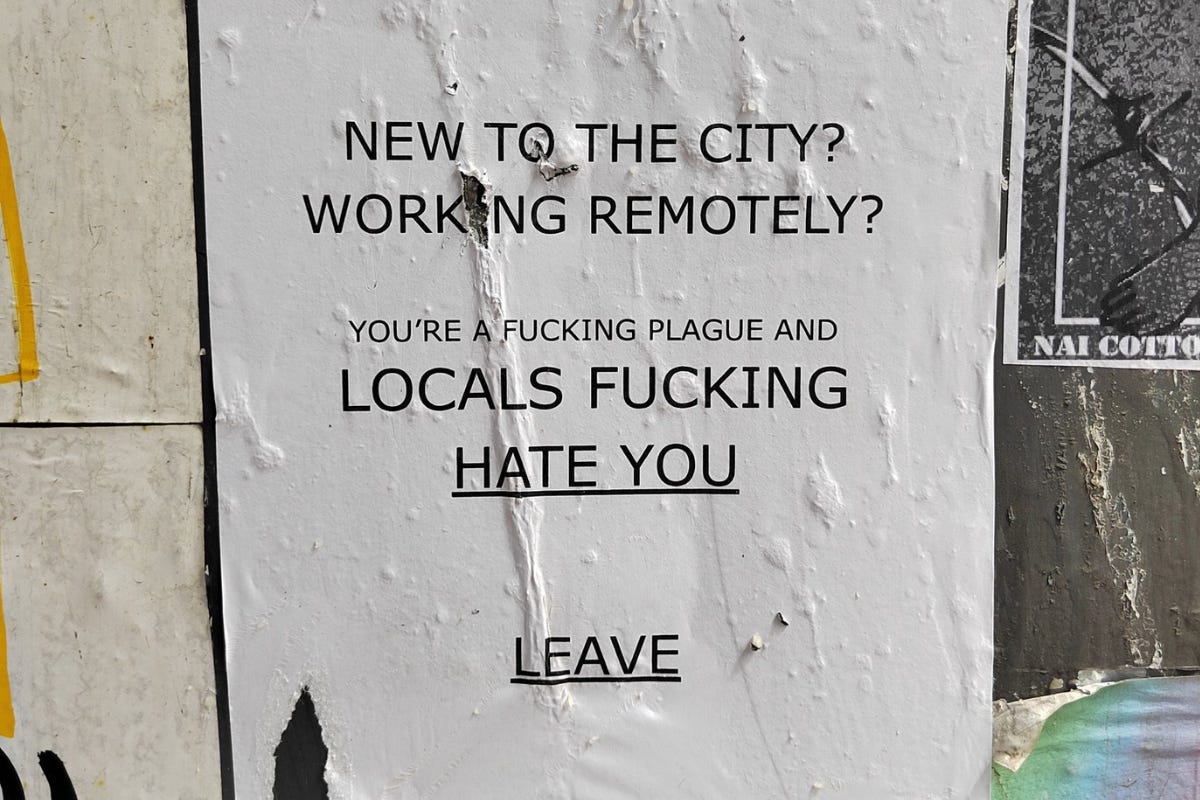

Earlier this summer, I came across a flier posted in Colonia Roma that read like this:

“New to the city? Working remotely? You’re a fucking plague and the locals fucking hate you. Leave.”

The vitriolic language took me aback, but it wasn’t anything new. I’ve been receiving comments like these on TikTok for over the last year. Simple videos of me having lunch with my Mexican girlfriend sparked accusations of being a “colonizer,” the same word used to describe Hernan Cortes and the conquest of the Aztec capital.

As someone who built a YouTube channel promoting curious, conscious, and considerate exploration of our planet, I initially didn’t know how to take such comments. I’d always tried to use my platform as a bridge between cultures and even after 100,000,000 views I had never received criticism remotely as negative, frequent, or personal as this.

Why the sudden change? Was it just TikTok? Xenophobia? Mexican society? Or was there something else happening that I was not aware of?

This past month, I got my answer. Multiple economic, social and historical forces have converged to make the presence of foreigners relocating to Mexico City much more controversial than I initially understood.

But first, a bit of context on how your author came to be here.

II - The Context

In the summer of 2020, I fell in love with a Mexican girl who lived in Condesa and moved down here to pursue the relationship. We spent the first year mostly in lockdown, and the self-contained, gorgeous, and tranquil neighborhood of Condesa felt like a relative bubble of safety in an unpredictable pandemic.

After nearly a decade of traveling the world, I was ready to stay in one place for a bit. I’d seen hundreds of cities in my travels, but Condesa and the adjacent neighborhoods of Roma and Juarez scored amongst the most liveable places I’d ever visited.

For the first time in years of restless wandering, I was content to sit still. I had quit YouTube and taken a massive pay cut in order to focus on writing. And Mexico City seemed like the perfect place to reduce my expenses and focus on writing while also immersing myself in my new host culture.

I enriched my Spanish with local slang and immersed myself in Mexican history, culture and cuisine. And as my intimate relationship deepened, so did my relationship with my girlfriend’s culture.

Then, after a year and a half together, we broke up. I won’t go into the details here, but suffice it to say that on top of heartbreak I suffered the jolt of uprootedness as my life in Mexico was suddenly turned upside down.

My most direct connection to Mexico was severed. The relationship that brought me here no longer existed. After a year and a half of socializing mostly with Mexicans, I no longer had a community. The angry TikTok comments started to take on a sting that was hard not to take personally. I felt unwelcome here. I debated going home.

But I decided to stay.

There were practical reasons - I had already registered as a temporary resident, rented and furnished an apartment, and created my monthly storytelling event, Cuéntame. But something else had happened in my year and a half here.

I fell in love with Mexico.

As I picked up the pieces from the breakup, I found the hidden gift amongst the grief. The relationship had brought me to one of the most fascinating cities in the world.

I knew that if I were to stay, I would have to forge a new relationship with Mexico. I stopped hanging out in Condesa and explored new corners of the city every weekend. I embraced the foreign community but also sought out new, meaningful relationships with locals and existing cultural institutions. And as I did, I saw a new possibility - to act as a bridge between the foreign and local communities.

The city has changed dramatically since I first arrived here in September of 2020. Back then, I felt like I was one of the only foreigners around. Every other building on Avenida Amsterdam had a Se Renta or Se Vende sign hanging out front. Landlords were desperate to fill vacant buildings and it was a buyer’s market.

Now the same neighborhoods are full of foreigners. Housing is scarce and rents are rising. English is spoken so widely that it is possible to bounce between gringo-friendly establishments without speaking more than a few words of Spanish.

While I have always been an enthusiastic promotor of my adopted home, I now see that the wave of visitors is bigger than most people realized - and it’s having real-life consequences that are altering the hopes and dreams of many average Mexicans.

III - The Issue

15 years ago, Tim Ferriss kick-started the digital nomad revolution with his book The Four Hour Work Week, in which he advocated a new concept called “lifestyle design.”

He encouraged white-collar workers to ask their boss to work from home once a week with the intention of eventually proving they could work remotely full-time.

His next recommendation was to achieve “geo-arbitrage,” or the ability to earn income in a strong currency like the dollar, while living in a county with a cheaper currency like Mexico.

At first, only the brave and resourceful attempted this “digital nomad” lifestyle. They congregated where the WiFi was strong and the lifestyle more comfortable and less expensive than back home. At first, this was mostly in South East Asian countries like Thailand or Indonesia.

Then the pandemic changed everything.

Corporate America went remote overnight. Suddenly millions of people with salaries pegged to the cost of living in San Francisco or New York were free to work anywhere.

Mexico was one of the only places U.S. citizens could travel during lockdowns. Initially, most escaped to the beaches of Tulum, Sayulita, and Puerto Escondido. But the wifi is not stable enough to work from these beachside towns. For that, you needed to go to Mexico City. Many did and were pleasantly surprised to discover a cosmopolitan and beautiful city that defied the stereotypes of American media.

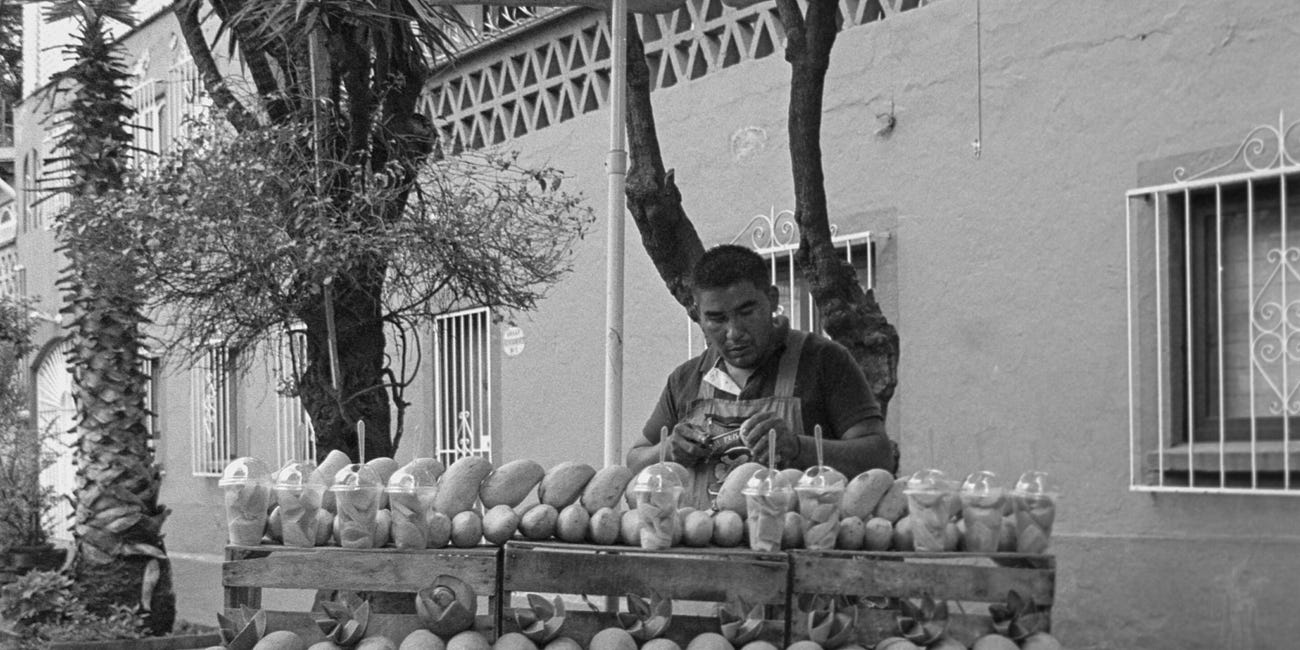

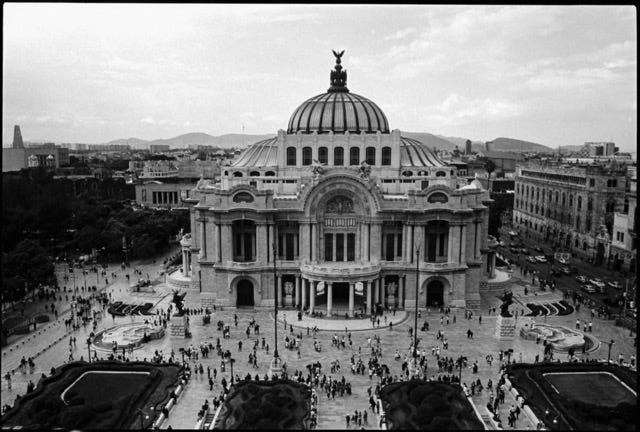

The appeal of Mexico City is clear. Few cities on earth rival its history, climate, architecture or food. And for remote workers, the location has added advantages.

Mexico City sits squarely within US time zones, making it easy to continue working for US companies. And when companies do require workers to return to the physical office, it’s only four hours to either LA or New York - closer to both cities than they are to each other. Mexico quickly became the third corner of a triangle connecting North America’s most important cultural centers.

I should note that I think there are many positive aspects to this. For too long, the flow of migration has been asymmetrically directed towards the US. But in the breath of two years, Mexico has effortlessly attracted what many countries actively compete for - highly-skilled workers and foreign capital (i.e. salaries earned in the US and spent in Mexico).

I’ve personally overheard many coffee shop conversations between foreign investors and Mexican entrepreneurs, and I don’t think that we will see the fruit of such collaborations for a few more years still.

Nevertheless, the sudden influx of well-paid remote workers is dramatically altering the landscape of the city, just as tech salaries did to San Francisco. Now the diaspora of tech workers is bringing these same effects to the world at large. And the clearest-cut example of what’s happening is here in Mexico City.

IV - The Bubble

The main factor is housing. Most foreigners stay in just a few adjacent neighborhoods - Condesa, Roma, and Juarez.

Condesa and Roma have long been popular with foreigners. Colonia Roma was developed by an Englishman, modeled on European designs, and representative of the larger Europhilia of the then-dictator Porfirio Diaz.

But these neighborhoods (along with all of the city center) eventually fell on hard times, specifically after the devastation of the 1985 earthquake. When middle-class families moved to newer neighborhoods, rents dropped and this area became accessible to the working-class.

Then came the artists - and with them, a process known as gentrification.

Mexico City began to gentrify 20 years ago. As modern apartments replaced the buildings destroyed in the earthquake, the rents started to rise again. Enterprising chefs took risks and built the restaurants that put Mexico City on the map of foodies worldwide.

In short, the neighborhoods became trendy and wealthy Mexicans started following the artists in the same pattern we have seen everywhere from Brooklyn to Berlin.

This, in turn, made the neighborhoods safer and more attractive to tourists. Social media posts were almost exclusively about these two neighborhoods, romanticizing the appeal of living in Mexico City at the exclusion less-sexy realities beyond.

And as this process spread from Condesa and Roma to neighboring areas, a large “bubble” of relative safety and affluence began to detach from the everyday reality of most Mexicans.

To be clear - this process was already happening when the pandemic struck. But during that initial moment of shock when many young people returned home and families failed to make rent, the housing market went through a huge shift.

Many landlords had empty buildings that they decided to convert into AirBNBs to cash in on the digital nomad boom. This in turn reduced the stock of available housing, pushing up prices with rising demand - thereby making these once-attainable neighborhoods suddenly out of reach for countless middle- and working-class Mexicans.

And while this injection of foreign money has its benefits, the concentrated way in which it is spent tends to exacerbate existing inequality.

For example, the same famous restaurants are on every tourist’s bucket list, concentrating profits to four or five chefs. Money spent on AirBNBs accrues with already-wealthy landlords, not working-class Mexicans struggling to get by.

What’s worse, those with power and influence often have little qualms about pushing out poor families (sometimes forcefully) in order to make hotels or housing for wealthier foreigners. The fact that this process of displacement is often initiated by government “beautification” projects using taxpayer money just fuels resentment.

All of this has been playing out against the backdrop of Mexico’s vast inequality, exasperation with the impunity of abuse from elites, and centuries-old divisions along ethnic and class lines.

In a place where wealth buys power, foreign influences overpower the indigenous, and the lighter skin affords preferential treatment, the sudden arrival of thousands of wealthy, foreign, predominantly white people pours fuel on the fire. And society pivots to accommodate them - at the expense of locals.

Thousands of Americans set off on their Mexico City adventure each day. And few realize what a shit-storm they are walking into.

V - The Tweet

The controversy first flared up last spring, when an American blogger casually tweeted a photo of a beautiful building in Roma Norte with the caption: “Do yourself a favor and remote work from Mexico - it’s truly magical.”

The response from locals was swift and severe. The nicer comments tried to make the commenter aware of how the “magic” of Roma and Condesa was far from universal. Many more commenters encouraged her to go home. The term “colonizer” was used interchangeably with “gentrifier,” both of which have been frequently applied to me on TikTok.

At first, I was defensive. Colonizer, like Hernan Cortes? Isn’t that a bit extreme? (For the record, I still think it is.) But the vitriol clearly resulted from deep underlying tensions that most foreigners - myself included - were unaware of. And the more I’ve dug into the issue, the more layers I have come to appreciate.

For one, most Americans are ignorant of the cultural baggage with which we arrive in Mexico City. Being called an ‘invader’ might feel extreme, but Mexico was invaded by the United States - 10 times.

The hymn of the US Marines literally begins with the line “From the Halls of Montezuma,” a reference to the Castillo de Chapultepec, the final battle in the US-Mexican War. It’s the Mexican equivalent of The Alamo, where the “Niños Heroes” (or “Boy Heroes”) were martyred fighting off the invaders. In the subsequent peace deal, the US took 51% of Mexico’s territory. But few foreigners realize how deep of a wound this has left on the national psyche to this day.

Secondly, there are huge asymmetries in privilege between Mexicans and Americans. Set aside the obvious economic disparities and just look at the differences in tourist visas. A US citizen is granted 180 days in Mexico visa-free. Many of today’s digital nomads are abusing this privilege by renewing this visa indefinitely rather than obtaining residency (which, by the way, is relatively easy).

Countless Mexicans risk their lives (and lose them) daily to get to migrate to the United States. Even getting a tourist visa is a massive hassle that requires money, time, background checks and suspicion that has no equivalent for Americans. This breeds resentment.

But perhaps the most important factor is also the most insidious. Call it an air of neo-imperialism. The overall belief that the United States is the best country in the world, something we are raised hearing in school and on TV. But it manifests as a subtle belief that if an American and a foreigner don’t speak the same language, the onus of adapting to the situation is on the foreigner. But in Mexico City, the Americans are the foreigners. And yet we still expect Mexicans to learn our language, serve our food and adjust to our needs.

Hence the intense reaction to a well-intentioned tweet. Another foreigner who probably doesn’t speak the language, respect the culture or understand the history romanticizes a small sliver of Mexico City while ignoring the major issues her visit exacerbates - while encouraging more people to do the same.

VI - The Hope

Despite all the controversy, I am hopeful for the future.

Let me be clear - foreigners like myself carry much of the responsibility in improving the situation in the short term. We are guests in this country and must act with appropriate respect. I’m going to dive into this in a follow-up article.

But I also encourage local critics to see the immense possibilities in this situation.

Mexico City is having a moment. It is finally receiving the credit it has long deserved. This is truly one of the great cities of the world, home to an unparalleled tradition of art, culture, and cuisine.

Great cities have brief periods where the whole world’s interest and praise and focused on them. Right now Mexico is the darling of the world. And I hope the aforementioned challenges don’t distract from the chance to take advantage of this.

Many critics decry that Mexico City is becoming less Mexican. Perhaps. But it is also becoming more cosmopolitan. And there is a tradeoff inherent within. As a place becomes more like the world, the world also becomes more like that place.

The question to me is not whether foreigners should come or leave. We can not reverse globalization, nor should we want to. We can only try to channel these forces towards more equitable and desirable outcomes.

I see a future in which the flow of migration between Mexico and the United States is more balanced. Where Mexico City becomes more closely tied to the other North American capitals. Where Mexican artists, artisans, and entrepreneurs can reach a more global audience. And where North Americans can become better visitors, immigrants and neighbors.

We are not there yet. There is still much to do. But right now we have the chance to learn from the mistakes of the past and build something better together.

I hope we do.

The more I write about this, the more complex I realize the issue truly is. It’s not just about gentrification - it’s actually about globalization, an inexorable process that cuts through societies with a double-edged sword.

I know there is more to address in than what I have written, but I will continue with two more parts: what you can do to reduce your impact while traveling to Mexico City; and how this issue is actually about the future of work and travel in a globalized world.

If you’ve enjoyed what you read, please share this article with a friend and consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support my ongoing work.

More soon,

Marko

NOTE: For more on this topic, see my subsequent posts:

Global Gentrification -- Are Digital Nomads Ruining Everything? (Part 2 of 4)

Hi everyone, welcome back to The Missive.

Should Mexico Tax Digital Nomads?

This week’s issue of The Missive is a continuation of a series on remote worker gentrification based on my experiences in Mexico City. Click here to read the first piece or browse all my past posts here. And please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support my writing.

The people who are using terms like 'colonizer' are cunts.

Yes - I'm using such a strong word because it's appropriate. You don't owe anyone an explanation for what you do - nor do you need to cater to first world brats complaining about gringos.

It's xenophobic bullshit - Americans can't complain about uncontrolled illegal immigration for fear of being called 'racist'... yet Mexicans can be unmitigated xenophobes and get a pass? No thank you.

Honestly, Mexican nationalism can be very regressive and nasty. I prefer other Latin countries where people aren't as full of themselves like the Mexicans. Why not try out Spain? You can live there without fear of North American aggros calling you a colonizer or attacking you for being a 'white male'.

Almost five years ago my husband and I sold our house in Seattle, got rid of most of our possessions and set out to become digital nomads.

Ironically, we were living in CDMX for three months when Covid hit.

Different thoughts about your newsletter and the topic itself, which we've given a great deal of thought during our travels and frequently write about in our own newsletter.

First off, I appreciate your thoughtful and nuanced take. Too often people seem to come down on one side or the other: Being a digital nomad is brilliant and is the perfect way to live! versus Digital nomads are selfish colonizers destroying the world!

In my opinion very little in life is black and white. It's mostly shades of gray and everything has pros and cons. They all need to be considered and since we all have different opinions and values, few of us are ever going to see the world the exact same way.

As for CDMX, I think right now there are a lot of pros and cons, and the cons are best addressed by government action. Sadly, that isn't something Mexico excels at. Even though we frequently use Airbnb, I have zero problem with governments using zoning to restrict them. That being said, I hope a balance is struck because I do believe the influx of American wealth is a net gain for CDMX, which is an incredible city that more people should see.

And I guarantee our presence over the past five years in places like Tbilisi, Georgia; Bansko, Bulgaria; Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina; and now Novi Sad, Serbia, are definitely welcome by locals. These are all cities and countries that have struggled economically and I firmly believe that our spending money in places like these are far far better than had we stayed in Seattle and kept our "wealth" there. We've always acknowledged we have a certain level of privilege no matter where we live. But we think the world is better off when we spread that "privilege" around to other places.

No, we aren't doing this for altruistic reasons. We think these countries and cities are interesting and we do enjoy a more affordable COL but we do try and be decent people and think before acting and care about our impact on local communities.

Looking forward to the rest of your thoughts.