Should Mexico Tax Digital Nomads?

How destinations can capture talent in an era of hyper-mobility

This week’s issue of The Missive is a continuation of a series on remote worker gentrification based on my experiences in Mexico City. Click here to read the first piece or browse all my past posts here. And please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support my writing.

The Promise and Peril of Hypermobile Workers

The remote worker gentrification debate has simmered down somewhat since the peak of America’s summer travel season. But the issues at the center of the local debate continue to be relevant worldwide.

Does the remote work revolution help or hurt cities? How do we resolve the asymmetries of mobility, income, and opportunity between nomads and locals? And what does fairness look like in an era where some can move where they want while others must move because they have no choice?

Which is what brings me to the question of “nomad taxes.”

I first spoke about this in my recent interview with Lauren Rezavi, in which she cited “nomad taxes” as one example of how governments can more effectively capture the wealth created by digital nomads and remote workers.

The basic idea is that local governments should tax a portion of remote workers’ income, just like they do for all other residents. After all, they are using publicly-funded services like roads, police, and public transportation.

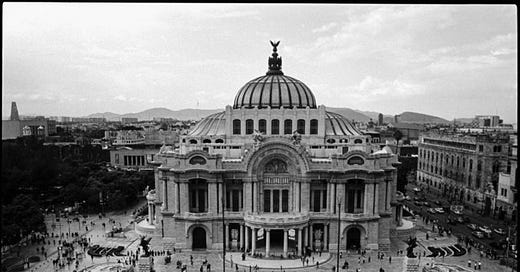

The remote worker gentrification controversy here in Mexico City has caused many locals to call for the government to tax, restrict or deport remote workers.

And while I understand the sentiment behind such demands, I fear that the hyper-mobility of digital nomads makes taxing them difficult.

After all, why would they agree to be taxed in Mexico if they can just move somewhere with no restrictions?

And this dynamic is one of the core challenges of globalization. Let me explain.

Offshoring, Remote Work and the Race to the Bottom

In the wake of the cold war, globalization went into high gear. No longer divided by an iron curtain, the world became a single market. And major corporations were able to cut costs by relocating their factories to cheaper countries overseas.

This “offshoring” of manufacturing jobs hurt western economies in a few ways. Beyond job losses, workers’ rights and environmental protections were bypassed as factories moved to countries with lower taxes, cheaper labor, and looser regulations.

China was an early recipient of these jobs as early as the 70s. As China became the new “workshop of the world,” it lifted 700 million citizens out of poverty and expanded its middle class from 4% of the population in 2002 to 31% in 2013.

But this caused wages to rise. Suddenly China wasn’t as “cheap” as it used to be. Once again, CEOs started looking overseas for alternatives. And many developing countries were ready to do whatever necessary to attract the investment China was losing.

This spurred the development of “Free Trade Zones,” areas created by governments to attract international investment and manufacturing through low (or no) taxes, regulations, or labor laws. Often these policies of deregulation were applied to the country as a whole (i.e. the Chicago Boys impact on Latin America).

Historically, these policies worked for ports like Singapore, Hamburg, and Gilbraltar. And nation states have been competing to be “business friendly” since the late 19th century. But recent, rapid advancements in transportation, communication and globalization has made the competition between countries ruthlessly competitive.

Modern corporations have the scale to move manufacturing jobs to whichever country has the cheapest labor and fewest restrictions. And this collective loosening of regulations and capital controls made international investment very volatile.

As a result, the slightest increase in tax, regulation, or cost was often enough to cause companies to abandon one destination for another. And many countries competed by gutting their public services, erasing protective restrictions, stripping away workers’ rights, and repressing wages - while collecting minimal tax from foreign companies.

Certainly, many modern free zones have leveraged this investment to become prosperous societies - namely the “Four Asian Tigers.” But more often, the well-being of locals was sacrificed to attract investment. And once somewhere else appeared cheaper or less restrictive, the investment moved overseas.

This process has been called a “race to the bottom” as countries bend over backwards to attract foreign investment at the detriment of their citizens. And by the time the jobs disappear, the damage has already been done.

And I’m worried something similar could happen in the race to attract remote workers.

Nomad Visa Vs. Nomad Taxes

As I mentioned in my piece on globalization and gentrification, while some Mexico City locals have described remote workers as a ‘plague’ that should ‘go home,’ dozens of other countries are offering cash incentives and visas to attract them.

Why?

Spain and Italy are both trying to lure remote workers to their depopulated countrysides. Places like Tulsa are offering cash incentives in the hope that these workers’ skills and incomes will revitalize their cities and towns.

And from my own anecdotal experience here in Mexico City, the influx of foreign investors, entrepreneurs and innovators seems guaranteed to create an economic boom that could drastically Mexico’s economic fortunes for the better.

The coveted value of these workers points to an emerging trend: Greater mobility gives remote workers the privilege of choosing where they reside. Countries are competing to attract them. And that makes digital nomads the knowledge worker equivalent of the manufacturing jobs countries competed for in recent decades.

But one major difference is that digital nomads do not bring ‘direct’ investment, like when G.M. builds a major auto plant in a country. Their investment is all ‘indirect,’ in that they are spending money within the country, similar to tourism.

Mexico has the seventh biggest tourism industry in the world, consisting of around 8% of GDP. And during the pandemic, that number was slashed by half. Which is why Mexico imposed virtually no requirements on visitors during the pandemic.

No negative COVID tests. No proof of vaccination.

Instead, the burden of the pandemic was placed on service workers, who have relatively little social safety net, no stimulus checks, and often no medical insurance. Local workers were required to remain masked while Americans partied like it was 2019, leaving the mess for the locals to clean up.

For better or worse, the plan was a ‘success’ in that Mexico became one of the most touristed countries in the world. Mexico City in particular is the most talked about destination of the year, inspiring extended sojourns from Brooklyn to Berlin.

But digital nomads are not tourists.

They stay longer and often distort the housing markets by increasing demand for short term rentals like Airbnb. But they also provide valuable skills, ideas and networks that many governments want to retain.

How can places like Mexico attract remote workers without sacrificing locals? And how can they tax nomads without pushing them away?

Hence my analogy of “the race to the bottom.” So what is to be done?

The essential issue in Mexico isn’t just that remote workers aren’t being taxed - it’s that most are not even legal residents. The majority of remote workers are here on tourist visas and staying in Airbnbs.

Nomads - like everyone - pay sales tax. Here in Mexico it’s 16%. And given that many of the short-term visitors tend to frequent the more expensive restaurants in town - Pujol, Maximo Bistrot, Contramar - they are generating significant sales tax alone.

But I fear that requiring these new residents to pay additional income tax in Mexico (or elsewhere) would almost certainly encourage nomads to move on to Medellin, Costa Rica, or somewhere else with no such restrictions.

Worse yet, the distortions already created in the housing market would remain. Apartments converted to Airbnbs are unlikely to return to low-income housing. Locals will be left with the damage long after nomads move on.

I wonder which scenario would have a more net-positive impact on Mexico: minimizing restrictions on nomads to maximize their spending here; or taxing them and risk losing these workers to a less restrictive destination?

This is something many destinations will have to wrestle with in the coming years.

The first step at least is clear. Destinations should be encouraging nomads to register as legal residents. Currently, self-employed temporary residents pay no income tax in Mexico (and only federal income tax in the US). This is enough of an incentive for many to regularize their immigration status. And bringing them into the system is an essential first step. But for a more lasting solution, we must think bigger.

A Local Patchwork for a Global Problem

The remote worker phenomenon is here to stay. Cities and countries are competing for the world’s top talent. And this raises a host of questions about the implications this has for fairness, citizenship and equality of opportunity.

However, I feel like focusing on whether nomads pay local taxes is missing the bigger picture. The largest tax evaders in the world are the multinational corporations that hire armies of accountants to hide their profits through shell companies, tax havens, and slights of hand like the infamous “Dutch Sandwich.”

The real issue is that technology has outpaced regulation, allowing companies and intrepid individuals to outmaneuver national tax frameworks. Nomads and multinational corporations are truly global. And the solution should be as well.

That’s why I believe world leaders need to work towards a global minimum tax.

President Biden has taken the important step of proposing a 15% global minimum corporate tax and uniting 130 countries around the idea. Together, these countries represent 90% of world GDP.

But until all countries are on board, there will always be jurisdictions that offer lucrative loopholes. Furthermore, this only addresses corporate tax.

Remote workers often mirror the jurisdiction-dodging behavior of their employers. Perhaps if we can get consensus on a global minimum tax for corporations, it will be easier to create a parallel concept for individuals.

I see no other way to address the global issues facing humanity. Climate change, migration, and taxes are all bigger than any one government. And we must expand our political and societal affinities to a planetary-scale in order to deal with them.

But as long as there are loopholes, tax havens, and citizenships for purchase, we will continue to see the privileged few take advantage of the opportunities of globalization while those left behind are stuck with the mess.

Nevertheless, I think Mexico is in a unique position to retain remote workers for the long term. But that’s a subject for a future edition of The Missive. Subscribe for more.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing The Missive with a friend or upgrading to a paid subscription to support my work.

Until then, I remain,

Your Man in Mexico,

Marko Ayling

Thanks for this--you capture the complexities well. I think that a digital nomad taxation probably isn't the solution. Aside from the difficulties of enforcing it, I do think it ultimately sends the wrong message to a population of people that can, as you say, simply go somewhere else instead. One way many American cities are dealing with such issues--though unintentionally--is with zoning for Short Term Rentals (STRs e.g. AirBnB). Cities (or neighborhoods within cities) will either have a lottery system for permits to operate an STR, or (as where I live) forbid them entirely. Therefore it would be quite difficult for a digital nomad to set up for 90 days in my town. (Although I am surrounded on every side by equally populated cities that allow them.)

Another question I have is this: whenever a government talks about additional taxation, I wonder 1) where will this money go? and 2) do you not already have enough? You mention that DNs use the roads and other public services just as residents do. But which taxation streams do the government already use to provide such services? If it's largely property taxes, then the DN is already contributing to the income of the STR property owner and ultimately *is* paying the property tax, and therefore for the infrastructure they're using.

Let's say, hypothetically, that the infrastructure is not very good. (I've been the Mexico City briefly, but I don't remember remarkably bad roads etc. while I was there like there are in Cuba, for example.) Then the government needs to invest in the infrastructure, which costs money which is made by taxation. How much money are they already earning? With sales tax at 16%, probably a fair amount. So the question then becomes what are they already spending money on that they don't need? At least in most countries I've spent any length of time (UK, USA, Spain) it seems a lot of tax money goes to waste and/or is used mightily inefficiently.

Perhaps, instead of creating an extra tax, it is possible to achieve what needs to be achieved while actually lowering taxes. Combine that with some restrictions on STRs and rent control, and you've got a scenario where the cost of living goes down for local residents, DNs are still incentivized to stay in the area, and their negative effects are minimized whilst their stimulation of the local economy is maximized.

As you say, this is of course more complex than that. But I believe the above represents a line of thinking I'm not seeing national or local governments explore, which is a shame, in my opinion.

I can't imagine how it could be enforced. I think the tourist visa should be changed to 90 days and residency required for DNs. We have been searching for a place to live for nearly a year and it's just next to impossible because of Airbnb and DNs. I'm a PR and my novia is local but everything is budgeted out of the range of local salaries. This will hollow out entire neighborhoods of actual Mexicans. We walked through Condesa and Roma Norte yesterday and it was like being in Europe.