Mapping The New Russian Diaspora

How the Russian exodus in response to War in Ukraine is reshaping cities worldwide

This week marks one year since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

This war has changed our world in countless ways: innocent lives lost, 8,000,000 Ukrainians displaced, the post-Cold War détente shattered, and the specter of nuclear war looming.

But there is one aspect of this war that has been less discussed — the diaspora of Russians fleeing their country, and the impact it is having on cities around the world.

Last year, The Missive began exploring the topic of remote worker gentrification in Mexico City. I believe it is much larger than a local issue and have attempted to connect the dots with similar dynamics in places like Lisbon and Bali to understand how remote work is changing the relationships between citizens and societies.

My research has revealed a world rocked by simultaneous shocks to its system: COVID, remote work, and deglobalization. But we have yet to mention the war in Ukraine and one of its byproducts — The New Russian Diaspora.

Since the invasion a year ago, an estimated 1,000,000 Russians have fled the country. It’s said to be the largest exodus since the 1917 Bolshevik uprising.

But why are they leaving? Where are they going? How are they impacting the places where they are settling? And how do their stories help us understand our changing world?

To find out, I made a call for stories on my Instagram, which was reposted by my friend Yulia Livshun, a Ukrainian blogger who writes in Russian from Mexico City.

A year ago, Yulia came to my monthly storytelling event in March 2022, whose theme happened to be “…and I was never the same again.” She tearfully shared stories from her followers - Ukrainians, Russians, and Belorussians - about how the war had changed their lives forever, transforming the event to transcend nationalism and connect on a human level.

Since then, countless Russians have left their country behind. I have followed their journey in news clippings about new Russian émigré communities forming around the globe. And while I see some similarities to the remote worker phenomenon, the Russian situation is entirely unique. Most are not ex-pats, but exiles. A century ago, they might have been called émigrés. Now many call themselves “relokanty.”

To learn more, I asked Yulia to repost my call for stories of these relokanty. Dozens responded with heartfelt stories of loss, hope, and isolation. I tried to distill their stories into the following article, which I hope will map out the causes, flows, and impacts of their travels. Names have been changed for privacy.

I want to be clear - in focusing this piece on Russian migration, I don’t want to diminish the Ukrainian refugee crisis or make a false equivalency between the two. Justice of the war aside, the Ukrainian migration is many times larger — an estimated 8,000,000 people have fled Ukraine, compared to between 500,000-1,000,000 Russians.

Nevertheless, with a million Russians suddenly appearing in cities across the world, it’s a critical element in my quest to understand what I call The Roaming 20s.

So if this is your first time reading The Missive, please support my work by subscribing or forwarding this to a friend. Let’s get into the article.

Russia’s Geopolitical Challenges

The Russian migration can’t be separated from geopolitical realities. Geopolitics is a political philosophy that argues that “geography is destiny.” It sets aside political ideals and focuses on how the fundamental realities of geography force leaders to respond to the strengths and vulnerabilities of the lands they govern.

In the case of Russia, two things stick out.

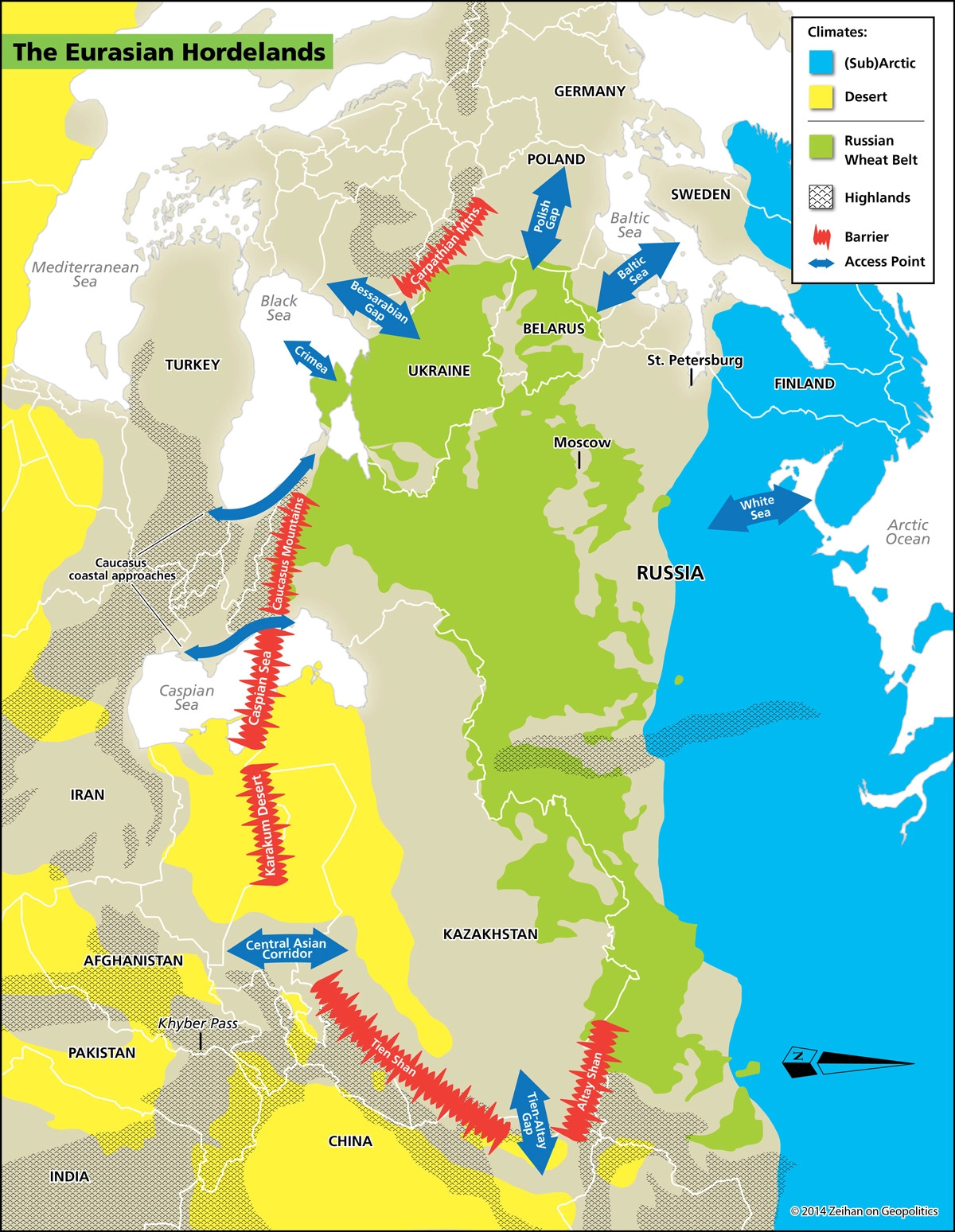

First, Russia is the largest country in the world. It spans from Asia to Europe and takes six days to cross by train. But it lacks natural barriers like mountains or oceans to protect it from attack. Historically, Russia has repeatedly been invaded from the west — seven times in the last 500 years — and always through the great expanse of flatlands known as the North European Plain. Ukraine sits squarely in one of these flatlands called the “Bessarabian Gap” between the Black Sea and the Carpathian Mountains.

For this reason, Russia has historically attempted to control these flatlands either directly or indirectly. In the Cold War, Russia achieved this buffer through the Warsaw Pact, which formed a ring of seven Socialist Bloc republics from the Baltic to Black Seas. But since then, these countries all became independent and some have joined NATO, eroding Russia’s control of the Flatlands. Russia is therefore surrounded by countries with a common language and history that Putin would like to reabsorb into Russia in order to re-establish this strategic buffer.

The second issue is depopulation. As with most developed countries, Russia’s birthrate started to decline in the 1980s. Except for Russia, it didn’t just start to decline — it totally collapsed. Between 1986 and 1994, Russia’s birth rate halved and its death rate doubled - all while the Soviet Union imploded. The result is one of the most rapidly aging countries in the world.

Having a bunch of old people hardly makes a society sound dangerous — but it actually does. Depopulation means Putin has a narrowing window to reestablish this security buffer before Russia runs out of young people — not enough workers to support domestic industry, not enough consumers for what Russia produces, and not enough soldiers to man their army. The invasion of Ukraine can be seen as Russia’s desperate attempt to push out its borders while it still can.

These two points complicate the migration story in two ways:

First, many of the places to which Russians initially migrated are precisely the places that Russia has historically attempted to control as part of this buffer. That means they often speak Russian, but their relationship with Russia varies from friendly to hostile. Some of these countries (such as Georgia) fear Putin’s army will target them next. Instead, they are being flooded with Russians fleeing Putin’s army.

Secondly, the war (and subsequent draft) worsened the depopulation problem overnight. Set aside the number of Russian soldiers killed in the war (as high as 60,000 by some estimates). Many of the 1,000,000 Russians who have left are precisely the educated, cosmopolitan, passionate citizens who could build a prosperous, democratic Russia. As they flee, they take their hopes for a better Russia with them.

Judging by Putin’s recent conscription of prisoners to serve as cannon fodder in Ukraine, this mass exodus is making depopulation a more immediate problem than anticipated.

I fear this makes Russia weaker, more unpredictable, and more dangerous.

Three Waves Make a Tsunami

At the risk of generalizing, I’m grouping this migration into three distinct waves:

The First Wave happened immediately after the invasion in February 2022. It was relatively smaller and consisted of many outspoken critics of Putin who feared being imprisoned for publishing “fake news”. This includes journalists, opposition leaders, and activists, some of whom are still escaping today. It also included tech workers or employees of foreign companies who could work remotely. Between 50-70,000 IT workers fled in the first month alone.

The Second Wave formed in July 2022. These migrants were often older and wealthier and may have needed time to arrange their departure, close their businesses, sell their homes, or let the children finish the school year. This wave included many of the 15,000 millionaires estimated to have left Russia in 2022. (More on this later).

The Third Wave was a direct result of Putin announcing a “partial mobilization” on 21 September (i.e. the draft). Every able-bodied man between 18-27 is eligible to be drafted, but the criteria have been continuously loosened. Draft notices are served at random and desertion is punished by up to 15 years in prison. The suddenness and scope of this announcement spooked hundreds of thousands of young eligible men (and their loved ones) to flee the country overnight - often hastily and without a plan. This is the largest wave. Most people I spoke to were in this category.

In total, between 500,000-1,000,000 Russians decided to flee in the last year. These three waves of migration - combined with a limited amount of potential destinations - has created a tsunami of Russians in many parts of the world.

Mapping The Exodus

Using interviews and news reports, I’ve tried to piece together a narrative from what was undoubtedly a spontaneous and rushed escape from Russia.

The largest single determinant of destination is simple: access.

Western sanctions further eroded the already weak “passport power” of Russians (#94 in the world) to a mere 87 countries that offered visa-free entry. Add in language barriers, limited savings, and the difficulty of gaining residency or registering a business, and the number of realistic options is even more narrow.

Although some were lucky to already have dual citizenship, visas, or residency in the European Union, United States, or elsewhere, most people I spoke with described a frenzied attempt to simply get outside the country before either being drafted, arrested, or detained by martial law.

The third wave was larger than the other two combined. At least 300,000 Russians fled immediately after the draft was announced. Flights out of Russia quickly sold out and prices to places like Dubai or Israel soared to between $5-10k USD. Many had no choice but to leave Russia by land. Large queues formed at the border crossings of Georgia, Kazakhstan and Mongolia, stretching up to 15km in places.

This caused the bulk of migrants to travel to countries that used to be part of the Soviet Union and/or border Russia directly: namely Georgia, Armenia, Uzbekistan and Kazakstan. In these countries, not only do Russians enjoy visa-free entry, shared history and language, and favorable exchange rates — many can even be reached by bus.

But the situation in each country is different. Let’s start with the Caucasus.

The Caucasus - Georgia & Armenia

Even outside of wartime, Georgia is an enticing destination known for its ancient culture, excellent food and wine, and cosmopolitan capital. It also has visa-free entry for Russians for up to one year and tax and immigration incentives for entrepreneurs and digital nomads. Georgia received 1/4 of those initial 200,000 migrants via the thin gorge at countries’ only border crossing, creating a line 15km long. An estimated 10,000 crossed per day, some bribing officials thousands of dollars to cross.

The capital, Tbilisi, was a top choice of the Russian intelligentsia, many of whom are against Putin. Olga, a 37-year-old jewelry designer from Ekaterinburg, chose Georgia because it was the easiest place to relocate her small business. But she says locals feel two ways about the new arrivals. Those who grew up during Soviet times speak Russians, while younger Georgians are reportedly not excited about hosting Russians - even those who oppose the war. The country of 3.7M people has spent three decades trying to establish independence and was invaded by Russia in 2008. Russia still occupies 20% of the country.

Furthermore, many of the second and third-wave arrivals are less ideologically inclined and have contributed to rents rising 80% in the last year, adding insult to injury. One local bar forces Russian patrons to check a list of boxes acknowledging their government’s misdeeds before entering.

Olga sees graffiti saying “Fuck Russians” all over the city. But that bothers her less than knowing that the situation could change any day, making her feel like she’s building her life on a powder keg. But she’s not sure where else she can go. Certainly not back to Russia, she says, “ППЖ — пока Путин жив, WPA — not as long as Putin is alive.”

Which is why many have opted for Armenia. It has been an easy transition for simple reasons - it requires no visa for Russians, can be reached by bus, and shares religious and linguistic traditions that have made locals more amenable to Russians. The capital Yerevan has a good balance of culture, weather, affordability, and plenty of émigrés who are putting down roots and building community. Many Russian companies have relocated to the capital and paid for employees to as well. It’s close enough to Russia for quick trips home to deal with paperwork or family emergencies.

Central Asia

The picture in Central Asia is more complex. These states were once part of the Soviet Union but have also been subjects of Russian colonialism, which creates a mixed reaction to new arrivals. Russian is spoken widely, and many have family ties here. Kazakhstan in particular received many ethnic Russians in Soviet times and by 1991 was 37% ethnically Russian.

But since the fall of the USSR, the flow of migrants has been one-directional — low-skilled Central Asian workers migrating to Russia to fill thankless jobs, where they encounter racism and discrimination. But since the war, the Kazakh government has received over 200,000 residency requests - a massive reversal in the flow of migration.

Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan is flooded with young Russian men. Luxury hotels are raking in profits, cheap hostels are packed to the brim, and bars are full of new arrivals looking for jobs, housing, and paperwork - or ideas of where to go next.

Kazakhstan shares the 2nd longest border in the world with Russia and some estimate it has received upwards of 300,000 immigrants. Many settled in border cities like Uralsk and Petropalovsk and are overwhelmingly male and of fighting age. Many are skilled workers like doctors (likely to be drafted) or engineers, like Ivan, from Nizhnevartovsk, Siberia.

Ivan chose Kazakstan because it was close to his family in Siberia. Long opposed to Putin, the draft was the final straw. He flew to Tuyumen, took a taxi to the border, and settled in Almaty, which feels both affordable and modern compared to small-town Siberia. He’s staying a year.

Anna K., 30, and her husband left Moscow last March for Uzbekistan, fearing a world war was about to break out. They were welcomed by locals. Once things cooled down, it was close enough for them to return home to tie up loose ends and vacate their flat. But once the draft was announced, the cheapest flight they could find out of Russia was a $1000 ticket to Tajikistan — 3x the normal price. Soldiers showed up at their door three days after they left to serve her husband a draft notice. They later moved on to Israel before settling in Thailand.

Like in many places affected by remote work, the influx of foreigners is affecting locals as rents rise and some see the return of a neocolonial dynamic. But here, these tensions are playing out against Putin’s attempt to recruit Central Asian immigrants for the war effort in exchange for fast-tracking citizenship. Some activists doubt Putin will make good on his promises while others report Central Asian migrants being detained by police, beaten, and forced to sign conscription papers. This touches a nerve, as it echoes the 1916 Uprising (Urkun), when czarist troops killed 270,000 Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, and other Central Asians who refused conscription during WWI.

As with Americans in Mexico, Russians in Central Asia are trading places with migrants. In time this may also force them to reckon with Russia’s colonial legacy, grapple with their status as neither tourists nor locals, and confront Russia’s asymmetric relationship with its neighbors. But most Russians I spoke with report nothing but positive interactions. Katerina, a psychologist whose in-laws are from Tashkent, says walking with her children through the Uzbek capital only elicits smiles and compliments.

For now, Central Asia seems to be a convenient, affordable first stop for those seeking a new life abroad rather than a place most intend to settle long term. Kazakhstan’s recent decision to clamp down on “visa runs” may cement its status as a point of transit to places further afield.

Eastern Mediterranean

When war broke out, many Russian and Ukrainian tourists were awkwardly stranded together in the Egyptian resort of Sharm al Sheik, where 1 out of 3 tourists were from the two countries.

But war changes priorities. Resorts are out and residency is in.

The most popular destination has been Turkey. Despite being part of NATO, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been courting Putin for years. And since the war, he has played both sides by selling arms to Ukraine, opposing sanctions on Russia, and trading directly with Russia for hard cash.

Turkey’s exports to Russia are up 60% since the invasion, Russia is funding a $20b nuclear plant in Akkyuy, and dozens of Russian companies (including Gazprom) are moving their European headquarters to Turkey. And Turkish ports have welcomed the yachts of Russia’s billionaires, including Andrey Molchanov, Maxim Shubarev, Roman Abramovich, and former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev.

Many Russians followed. Some to Istanbul, but many more to the resort town of Antalya, now dubbed “Moscow on the Med.” The area has always been popular with Russians, but the good weather, friendly locals, and easy residency requirements make it a prime destination for emigres. The number of foreign residents in Antalya Province has more than doubled in two years to more than 177,000 — including more than 50,000 Russians. In November alone, foreigners bought 19,000+ properties in the area, the highest in Turkey after Istanbul.

But despite Turkey’s charms, Natasha worries the Erdogan is making it harder for foreigners to get residency to pander to his base ahead of the elections. She is hoping to acquire a second citizenship and is applying for a freelancer visa in Germany to move to Berlin. Others have relocated to Cyprus, as well as the Balkan states of Serbia, Croatia, Moldova and Macedonia, all of which offer visa-free entry, good weather, and a lower cost of living.

Another popular destination is Israel, specifically Tel Aviv. Many Russians are of Jewish descent and in 2022 over 70,000 citizens of ex-Soviet states made ‘aliyah’ — a 23 -year high of immigration under Israel’s “Law of Return.” The majority are between 18 to 35 and are “professionals in fields where there is a labor shortage in Israel, such as medicine, engineering and education,” according to the Jewish Agency. Despite Israel being expensive, Anna K. says most Israelis are kind towards all immigrants because they understand how hard it is to start from scratch.

Further Afield

Beyond the most popular destinations, a few others stick out.

Dubai has emerged as the top choice for wealthy Russians who are bringing in so much cash it’s making even Emiratis blush. Property purchases by Russians in Dubai were up 67% in just the first 3 months of 2022, causing rents to surge 27% year on year as the ultra-rich use cryptocurrencies to circumvent capital controls and move their wealth outside of Russia.

Some of this is being reinvested into once-abandoned projects like the Dubai Pearl, a $4 billion dollar luxury development that stalled in the 2009 financial crisis. But the US Treasury Department just issued an alert warning of money laundering by Russian oligarchs in Dubai and rising rents make the already-pricy metropolis unaffordable for the many South Asian migrants who keep the city running.

Surprisingly, Argentina has emerged as a popular destination for pregnant Russian women seeking “birth tourism,” or having a child in a country to obtain citizenship. Argentina has no visa requirements for Russians and has received over 10,500 pregnant Russians in the last year. Katya, 31 from Novosibirsk, says this shocks some Argentinians, who see their country’s chronic financial crisis as something to escape. But Argentina does offer relative passport privilege, with visa-free access to 171 countries (versus 87 for Russia).

It has spurred a profitable cottage industry in Birth Tourism packages provided by tourism operators in Argentina offering flights, Spanish lessons, and help arranging hospitals for delivery. Economy packages start at $5,000 USD, while First Class goes for $15,000. One flight last week had 33 pregnant Russians onboard, many in the final trimester. But local authorities are starting to clamp down on the practice and recently uncovered a multi-million dollar scheme to defraud pregnant Russian women with fake documents.

Finally, Bali. Since the pandemic, the small island in Indonesia has suffered first from a complete absence of tourism, followed by a wave of pseudo-spiritual-influencers who have turned the once-idyllic paradise into a social-media fueled inversion of Eat Pray Love. This intersection of neocolonialism, spiritual bypassing, and cringe-worthy Instagram posturing has been well documented by the meme account Ubud on Acid. But lately, their attention is on the Russians arriving on the island in record numbers.

Bali’s immigration office issued 71,000 residence permits to foreigners last year — 29,762 of them were Russians, nearly half the total and over 3 times that of the next largest country, Australia. Thousands of Ukrainians have also come to Bali, attracted by its digital nomad lifestyle. And 10,000 kilometers from the front, citizens of both countries in uneasy coexistence at co-working places like Parq Ubud.

What Comes Next?

The list could go on. I barely discussed those in Mexico, the US, Canada, or the EU. But what started as me trying to connect tangentially related articles has ballooned into 4,000 words about an exodus that still is very much in progress. I intend to return to this subject in the future.

Thank you to all the Russians who shared their personal experiences with me. I hope I was able to put your story into a larger context. I know that in attempting to achieve both breadth and depth in some places I did neither. But I hope this is a start to mapping this diaspora. If you found this article helpful, please forward it to a friend.

Special thanks to Yulia for connecting me to her Russian audience to discuss a subject that impacts her personally. I know that many Ukrainians are tired of being asked to empathize with everyday Russians when their cities are being destroyed and loved ones are being killed. This week in particular hangs heavy in Ukrainian hearts, and I appreciate her willingness to help me.

To the rest of us, I hope this article has helped show the human impact of the war on everyday Russians whose lives have been turned upside down by a leader they oppose starting a war they don’t support. I suppose I empathize with them because I know that if America ever slipped into fascism, many Americans would be in a similar position.

Putin has turned Ukraine into a battleground. He has also turned Russia’s best and brightest into exiles from their homeland, scrambling to piece their lives back together abroad. If there was one theme I heard repeatedly, it was the gratitude for being welcomed into neighboring countries when so many others closed their doors.

What happens next, nobody knows. The Western media is speculating that China might start arming Russia. Most believe it will get worse before it gets better.

And as for those I spoke to, none expected to go home any time soon - if ever. Most expressed plans to move somewhere else later this year. Few had anything resembling a long-term plan.

Perhaps the whole situation is best summed up by a Russian proverb: Нет ничего более постоянного, чем временное.

Nothing is more permanent than a temporary phenomenon.

This is excellent journalism. I wonder what the numbers would be in the top recipient countries of the Russian diaspora if you updated them today?

One small quibble: the exodus of artists and professionals from Russia due to Putin's aggression in Ukraine didn't begin with the 2022 invasion - it began with the 2014 invasion. I know many who saw the writing on the wall and decamped to Cyprus after Putin annexed Crimea.

Fascinating insights. Living in the Balkans last year I saw for myself the rise of Russian immigrants. And I'm told that Malaysia -- our current home -- has been very popular with Russians fleeing the country.